Mary Jane (as she is named in the records) was born in 1827, in London (St Pancras). In the 1830s, the family evidently lived in France - from later censuses, at least three further children, Frederick, Augusta Elizabeth and Walter were born there (probably in Boulogne, which is specified as the birthplace of one of the children in one of the censuses).

At that time, it was cheaper to live in France than in England, so I surmised that it was financial difficulties that had caused the Cooper's to move to France. And in fact, there is some evidence for that: at the end of 1829, a partnership was dissolved between Nathan Chopping & Joseph Sidney Cooper, who had been japanners in London. (The name Cooper is common, but the combination Joseph Sidney Cooper is distinctive.) That suggests that their business was in some sort of trouble, which could account for the Cooper family leaving for France.

The Coopers moved back to England to settle in Hastings in about 1839. (I have an idea about how that happened which I will mention below.) Joseph Cooper had the Marine Library at least from October 1839, when an announcement of the death of another daughter, Ann Maria, appeared in the local newspaper. From 1839 on, the family's finances appear to have been secure.

Associated with the Marine Library was a 'Bazaar', which seems to have been the "Foreign and British Depot of Berlin Patterns and Materials for Ladies' Fancy Works" mentioned on the title page of Marie Jane Cooper's book. The title page gives the strong impression that Mr Cooper ran that part of the business as well as the Marine Library, and an ad in 1840 was placed by 'J. Cooper of the Old Established Bazaar and Royal Marine Library'. But I am certain that the Bazaar was Mrs Cooper's domain. In the 1841 census, Joseph is listed as 'Librarian' and Anna Maria as 'Toyshop Keeper' - though the layout may be intended to suggest that Joseph Cooper had both roles and Anna Maria was (just) his wife. (In the same census, Isaac Hope and his son George Curling Hope, who kept a Fancy Repository and Berlin wool shop in Ramsgate at that time, are described as 'Toymen' - 'toy' seems to have included fancy goods and general fripperies such as Berlin wool.)

The Marine Library's main function was of course as a library. An ad in 1840 gives a table of subscription fees, for periods ranging from one week up to one year, and for one person, two people or a family. Newspapers could be borrowed for a week, for a shilling (5p) and subscribers could borrow up to two volumes at a time. After Isaac Hope took over the Marine Library, he advertised it as "The largest reading room in the town, remote from Street Traffic, and having a splendid Sea View." I imagine that it catered mainly for visitors to the town. As well as a lending library, it seems to have provided a comfortable place to meet people, read the latest books and view the sea - a very useful amenity on a British seaside holiday, when good weather is not guaranteed.

It gives a comprehensive description of the Library's facilities:

This Library will be found the most commodious in Hastings. The leading Journals of the day lie on the table, as well as all Periodicals of merit; comprising, the Edinburgh Review, Quarterly, New Monthly, Blackwood, &c. Road Book, Gazetteer, Court Guide, Maps, Dictionaries, &c.

J. S. COOPER has on sale every description of articles in Stationery, useful and ornamental. The Library consists of works of Biography, History, Divinity, Poetry, the Drama, Novels, Romances, &c.

A large assortment of elegantly-bound Books, Albums, Blotting, Bible, Prayer Books, Church Services, Pietas, &c., much under the ordinary charge. Periodicals supplied on the day of publication. Writing Desks and Work Boxes at reduced prices.

In addition Mr Cooper offered pianofortes for sale or hire, and "Bagatelle Tables, Telescopes, Globes, Guitars, Backgammon Boards and Chess-Men." He was also a local agent for the Western Life Assurance Society, and offered information to "Visitors in want of Houses or Apartments", so acted as a kind of Tourist Information Office.

The ad in the 1847 Guide goes on to describe the Berlin Wool Depot (again without mentioning Mrs Cooper):

The ad in the 1847 Guide goes on to describe the Berlin Wool Depot (again without mentioning Mrs Cooper):

Adjoining the Library, is the old-established German and Berlin Wool Depot, at which will be found the largest assortment of Wools, Canvasses, Finished Needle Work, and Netting Silks, Tassels, Cords, Ivory Work from Paris and Dieppe, and a great variety of other articles for the Work Table, &c., imported direct from the Continent.I think that Marie Jane Cooper must have worked in the Berlin Wool Depot before she published her book in 1847, and it seems much more likely that Mrs Cooper ran that side of the business than that Joseph Cooper ran it as well as the Marine Library. And in fact I eventually found solid evidence for that. This report appeared in the Hastings and St Leonards Observer in 1879:

Mrs. Anna Maria Cooper, another old inhabitant, died on the 15th inst. at her residence, Walland's Lodge. She was the widow of the late Joseph Sidney Cooper, Esq., and mother of Major de Brabant Cooper. She was a daughter of Mrs. Roe, of whom I had knowledge as far back as 1824, when she kept a fancy repository adjoining the old warm baths in the Fishmarket. Mrs. Roe afterwards removed to a more prominent position at 1, East-parade, and at her death, her daughter, Mrs. Cooper, carried on the repository in connection with Cooper's Library, the latter superintended by her husband. Mr. Cooper, on retiring from business, invested some of his capital in the erection of the first houses on the east side of Warrior-square, to which, for a time, was given the name of Belgravia. He was a man of refined taste; and, as an active member of the Mechanics Institution, his services were conspicuously valuable when the said Institute in 1853 held an extensive and unique exhibition at the St. Leonards Assembly Rooms. Mrs. Cooper survived her husband's death a considerable number of years. and at her own death had attained to the age of eighty-one. It is but a few weeks ago that the old lady called on me, specially, as she said, to say Good bye! and to wish me and my family well; as, in all probability, it would be her last opportunity. This mark of respect from one who was apparently in her usual health, but who was destined so soon to quit an earthly sphere, seems now to possess a peculiar significance.I think that Mrs Roe's death enabled the Coopers to return from France and take over her business. A Mary Roe, born in 1772, was buried in Hastings in June 1839; this may be Mrs Cooper's mother, and the dates fit. It may be significant that Joseph Cooper always refers to the Bazaar and Berlin Wool side of the business, but not the Marine Library, as 'old-established' - he may have set up the library when the family arrived in Hastings, while Mrs Cooper carried on her mother's business. But I believe that Joseph Cooper owed a lot of his subsequent prosperity to his mother-in-law and his wife, even though he never mentioned either of them in his ads.

In 1849, the Hope family moved from Ramsgate and took over the Marine Library and Bazaar. Presumably, Joseph Cooper made enough money from the sale of the business to live on comfortably - in the 1851 census, he is listed as a 'Proprietor of houses'.

Meanwhile, what happened to Marie Jane Cooper, the starting point of this story, after she married John Edwards in 1847?

I said in the last post that in 1851, the Edwards were living in New Street, Birmingham, where Marie Jane was a Dealer in Fancy Goods and Berlin Wool. John Edwards was a bank clerk, which was probably his occupation before they were married. Also in the household were two children, two shop assistants, and two general servants.

The Edwards eventually had twelve children:

Annie Marie, 1849

George Joseph, 1850

Lizzie Augusta, 1851

Helen Constance, 1853

John Sydney, 1854

Catherine Blanche, 1856

Arthur Frederick, 1857

Ernest Walter, 1859

Herbert Alfred, 1861

Beatrice Mabel, 1864

Frank Percy, 1865

Hugh Leslie, 1867

The Edwards carried on the business at 48 New Street for another 20 years, though by 1871, Ann Ellis, one of the shop assistants, had become the manager, which perhaps allowed Mrs Edwards to slow down a bit. And by 1881, they had downsized the business considerably, though still living in part of 48 New Street with their youngest daughter Beatrice, two shop assistants and two domestic servants. Ann Ellis and her sister Frances, who had also been living as a shop assistant at 48 New Street, had set up in business as Ladies Outfitters elsewhere in central Birmingham.

In 1882, a notice appeared in the Birmingham Daily Post to say that Mrs John Edwards was retiring and selling off her remaining stock. She was by then 55, and it may be that John Edwards had recently died, though I have not been able to find any evidence of the date of his death. By 1891, she was living in Hastings again, a widow, with her daughter Beatrice. She was living on her own means, so the business in Birmingham had evidently been successful enough to provide funds for her retirement. I think that she returned to Hastings in the early 1880s because her brother was living there with his family. He was the grandly named Major Frederick Sidney de Brabant Cooper, mentioned in the 1879 report above about their mother Mrs Cooper - he was evidently a well-known public figure in Hastings.

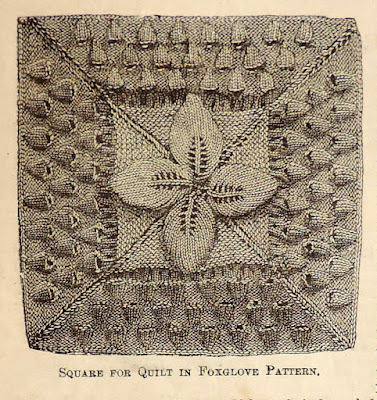

I don't know when Mary Jane died, though I can't find her in the 1901 census, nor any indication of what became of Beatrice. But I think it's worth celebrating the fact that three generations of women made a successful business from selling Berlin wool: her grandmother Mrs Roe and her mother Mrs Cooper in Hastings, and herself in Birmingham. They contributed to the popularity of knitting as a leisure pursuit for Victorian ladies. And Marie Jane Cooper added to the literature on knitting and crochet available to these Victorian ladies. For modern knitters and crocheters, it is her book, published in 1847, that is her main achievement, but probably for her it wasn't an important part of her life compared to setting up a successful business in Birmingham, and running it with her husband for over 30 years, while raising a large family. She must have been a tremendously energetic and capable woman - very far from the stereotypical image of a Victorian lady.