|

| Weldon's Practical Needlework No. 2 |

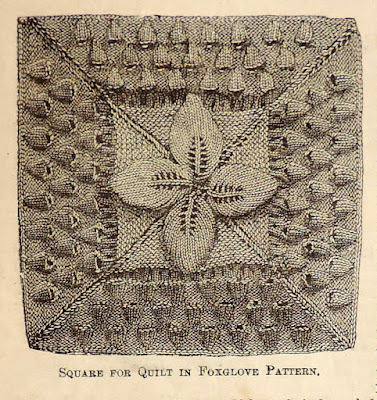

First is a pattern for a knitted quilt square in Foxglove pattern, described as 'exceedingly pretty'.

I recognised the image immediately, because I had seen one very like it when I was trying to find the pattern used for a 19th century bedspread - I found the image in an Australian newspaper, the Australian Town and Country Journal, published in Sydney, also in 1886. And now that I compare the two, the images are exactly the same - the Australian newspaper lifted both the text and the image from Weldon's Practical Needlework, in a cut-and-paste job. And I can't see any acknowledgement to Weldon's. To a former academic, that's really shocking behaviour - blatant plagiarism. On the other hand, much of the wording of the pattern is taken in turn from an earlier book, Needlework for Ladies for Pleasure and Profit by 'Dorinda', though Dorinda didn't illustrate it. So Weldon's aren't entirely innocent of plagiarism themselves. Victorian morals weren't quite as pure as some people claim.

Another pattern in the magazine is my favourite lace pattern. I started out thinking of it as Print o' the Wave, but I now think that that is only its Shetland name - in Victorian knitting books, it seems to have been called Leaf and Trellis (if it was given a name at all).

The description says: ' This is a very favourite old pattern for window curtains, cotton antimacassars, bread-tray cloths, and other articles. It is here rearranged and improved, and the veining of the leaves is carried symmetrically upwards." (Following a tradition beginning with Mrs Gaugain, the sample is shown upside down, with the cast-on edge at the top - I suppose because it looks more like a pattern of leaves that way.) The claim of symmetry in the pattern is because some of the decreases are right-leaning (knit 2 together) and some are left-leaning (slip 1, knit 1, pass the slipped stitch over) so that in the 'leaves' you get a line of successive decreases, all leaning the same way, and then a line leaning the other way. In earlier versions of the pattern (Jane Gaugain's, for instance), all the decreases are done by knitting 2 together.

So it may be that, as claimed, this is an innovation, and the first version of the pattern to have symmetrical decreases. Or it could be that the magazine has 'borrowed' the improvement from an earlier publication - I'm reserving judgement.

And the other pattern that I particularly noticed was for a Balaclava cap, 'a most comfortable cap for gentlemen travelling or for shooting excursions.'

It's knitted in navy blue Berlin wool (merino), with red stripes, on No. 10 bone needles. I would like to believe that the pattern was written for this magazine, but the image seems very familiar - I'm sure I've seen it before, but can't remember where. Maybe I have seen it in a later publication, but I'm not very confident - this might be another case of 'borrowing'.