|

| Knitting & Homecraft magazine, No. 4 |

We have several issues of Knitting & Homecraft in the collection, and in fact we already have this one. It was published monthly, and this was a February issue - but which year? It's evidently some time in the 1970s, by the styles, but the year isn't given. It isn't in the British Library catalogue either, which would give some dates. I've tried looking for clues in the magazine before, but I went through this one again, carefully looking for a mention of the year. Couldn't find one. It must be 1971 or later, because the price is decimal (30p), and I think it's early 1970s rather than later.

But looking through the magazine, I was struck by the claim that the Aran cardigan on the cover could then be knitted for 'around £5', which seems astonishing now. The yarn specified was good quality, too - Blarney Bainin Wool, Irish pure wool specifically intended for Aran knits. The pattern is headed 'Forever Arans': "These beautiful traditional stitch cardigans will always look right, feel right and be right for wherever you are. They would be very costly to buy, but these can be made for around £5 from our pattern." The editorial at the front also makes similar points: "we had in mind those of our readers who like good top fashion garments, yet cannot afford to pay high prices for the ones sometimes seen in the shops....... they are in pure wool, which will last for a very, very long time." Aran knits were very popular in the late 1960s and early 1970s for hand knitters (though not really 'top fashion', I think). The magazine was quite right about that last point - an Aran cardigan or sweater knitted in the 1970s could very well still be wearable. (I've got one myself (here), though it's not really a traditional Aran.)

I think the £5 cost reinforces my feeling that the magazine is from the early 1970s, rather than later. There was huge inflation in the U.K. around 1973-6, and according to the Bank of England's historic inflation calculator, the 2017 equivalent of £5 in 1970 is £73.53, but £5 in 1976 would only be worth £34.21 now.

My guess for the date of the magazine is 1971 or 1972, but I'd like to know, to catalogue it properly. I don't think the magazine lasted more than a year, in fact - we have (most of) issues 1 to 12, and I suspect that it folded after that. The content suggests that they hadn't quite worked out who their readers were. They included 'Homecraft' in the title, but in fact there is very little that isn't knitting - just three short pieces on tatting, embroidery and gardening. So anyone looking for cooking, say, as part of the 'Homecraft' would be disappointed.

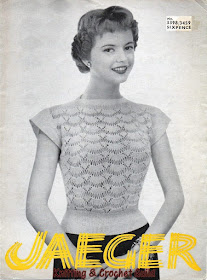

Another knitting pattern that caught my eye is this dress in random-dyed yarn (Jaeger Spiral Spun).

There are a few other designs for random yarns in the magazine, and they all show similar patterns of stripes in some areas and large patches of one colour in other areas - random yarns were very popular for knitters in the 1970s, and these unpredictable patches of colour were a desirable feature. (Now, colour pooling is something to be avoided.) The overdress is machine knitted, and again I wonder if the magazine was judging its readership correctly. Presumably they thought that including both hand and machine knitting would increase readership, but I suspect that most machine knitters would prefer to buy a machine knitting magazine (there were several being published then). And if a hand knitter saw this design and liked it, it would be frustrating to find that it was only for machine knitters. If I'm right that it only lasted for 12 issues, it never attracted readers in sufficient numbers. And now it is almost completely forgotten, except in archives like the Knitting & Crochet Guild's collection.